The Trail That Wrote Texas History

An array of keyboards, drum kits and microphones make an organized chaos in the shelves of self-proclaimed Austin history nerd and music producer Brian Beattie’s studio. But between the pianos and speakers stands something unexpected — two 48-foot scrolls depicting the story of El Camino Real de los Tejas. It’s the visual half of a show he performs that tells the story of the trail. This is where Beattie’s love for music and history meet.

“I just wanted a way to tell a story of the Camino that shows how it goes deep in the past and goes into the future and there's so many stories that we know that we don't necessarily know are tied to the Camino,” Beattie says.

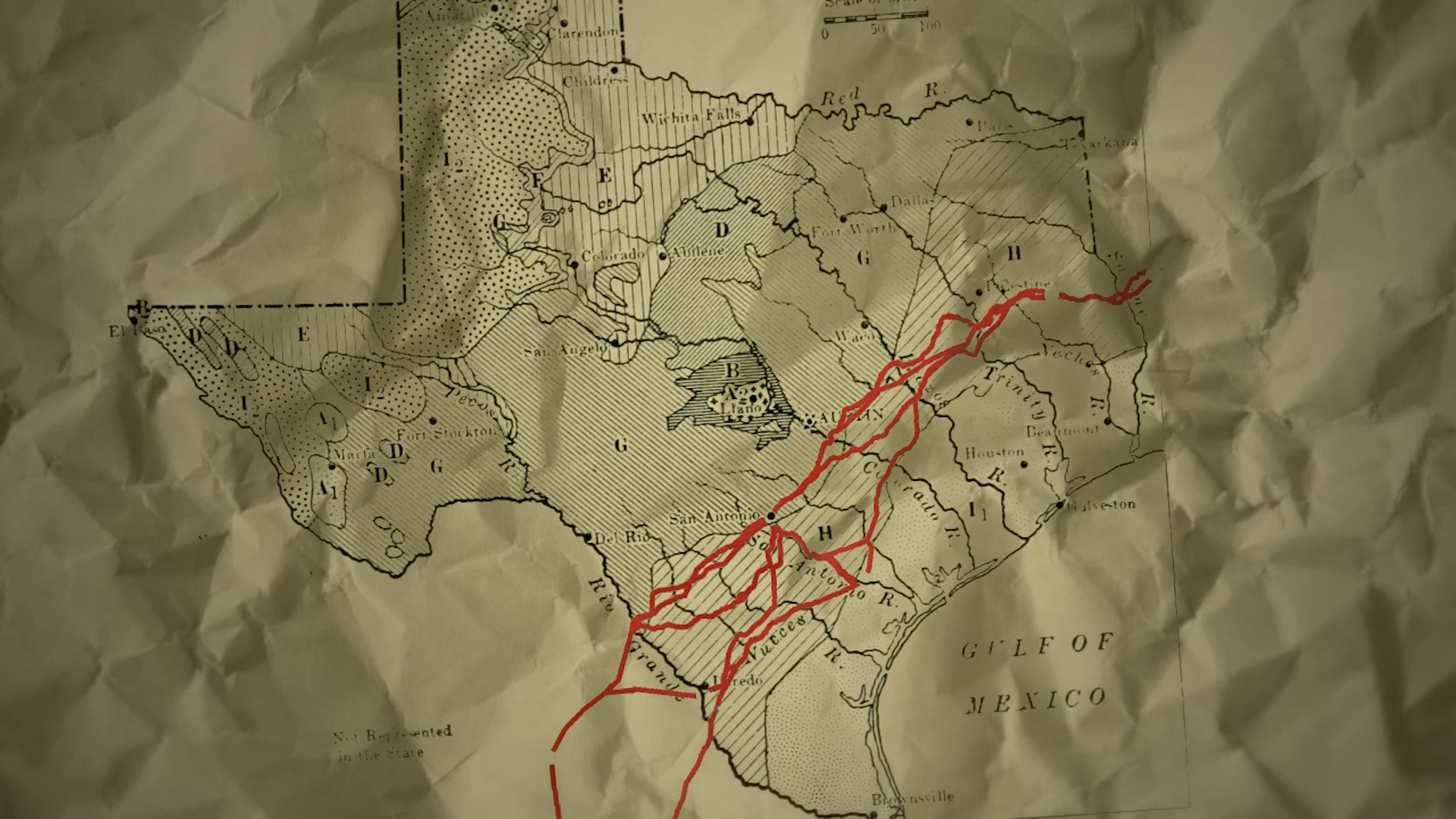

El Camino Real de los Tejas is a major trail that was used by travelers to explore land in Texas and Louisiana. The routes of the trail extend from Guerrero, Mexico through southwest Texas in Villa de Dolores, Laredo to Natchitoches, Louisiana. The trail was designated as a national historic trail in 2004. Steven Gonzales is the executive director of the El Camino Real de los Tejas National Historic Trail Association. He says the history of Texas can be found along its branching routes.

“The Camino Real de los Tejas is the road that led to the founding of Texas,” Gonzales says. “Originally, it was a Native American footpath that was later followed by Spanish explorers, French explorers, Anglo settlers coming into Texas, even African-Americans seeking freedom from slavery in the American South."

The routes of the trail extend from Guerrero, Mexico through southwest Texas in Villa de Dolores, Laredo up to Natchitoches, Louisiana. The trail was designated as a national historic trail in 2004.

But many are unaware of this history, according to Gonzales. He is concerned that lack of knowledge may lead to some of it being lost.

“A lot can be lost, unfortunately, if people are unaware of what they actually have in their possession,” Gonzales says. “Just south of Austin in San Marcos, there's a community that is named after a route of the trail. Sadly, that development, even though it named itself after the trail, in some sense it didn't understand the value of what it truly had.”

Prior to the community being built, Gonzales says there were physical remnants of the trail on the land. However, the development led to the loss of these remains.

That’s what drives both Beattie and Gonzales to preserve the history of the trail, including uncovering paths through the heart of Dove Springs. They are working to document and confirm a branch of the Camino Real along Pleasant Valley and Nuckols Crossing. Currently, this path isn’t officially recognized as part of the Camino Real route. But the pair believes there is enough written and physical documentation to get it linked to the recognized route.

“That pretty much aligns with the study route we're looking at,” Gonzales says. “Which is not an officially designated route of the trail, but something that we're looking at as a study route that could become an official part of the trail.”

According to the El Camino Real de los Tejas ArcGIS site, the trail crosses right through the George Morales Dove Springs Recreation Center. By using a combination of historical maps and Google Earth, Gonzales and Beattie are able to estimate where property lines start and end in relation to the Camino Real. A new apartment complex sits along the route of the old path, revealing some of the geological ridges that once shaped the trail.

Gonzales says while the most fun part of learning about the Camino Real is exploring where the trail now sits, the important part of this historical work is the research done beforehand.

Gonzales (left) and Beattie (right) inspect an old tree trunk. Features in the landscape like old trees and impressions in the earth can tell researchers a lot about the history of the area.

“That's what you do,” Gonzales says. “You do that historic research first, then you do the archeology after the fact to confirm, hopefully, that there might be some sort of an artifact that will say, ‘Yes, this is in fact linked to what you discovered historically.’”

For Beattie, the research he conducts about the trail shapes the stories he tells through his music.

“I loved that you're kind of sticking the magic of the place into the song and try to turn it into something that reflects all those stories,” Beattie says. “It's a big challenge, but it's like, I love that you can attempt to make it come alive and maybe get someone to do some more research about whatever it is.”

But to confirm what’s in these older accounts, Gonzales and Beattie have to get out in the field, searching for markers in the landscape. This includes identifying living fence rows, dating nails and trees, and finding swales–a straight depression through a waterway that can indicate an old route.

“They refer to people like us as rut nuts,” Gonzales says. “You're looking for those old ruts, those old swales, things like that, that is the physical remnant of the road.”

Beattie and Gonzales say archaeology also plays an important role in the task of looking for these trails because you never know what artifacts you will find. However, there’s one thing commonly dismissed throughout daily lives that can say a lot about a land’s history: oak trees.

“We're looking at the old oak trees like that because of their longevity, how long they've been alive, you know, and what kinds of history they may have seen,” Gonzales says. “They would have been great places for people to, break and live nearby and when they're working, have their lunch and that kind of thing underneath for, for many, many years.”

Beattie and Gonzales say that not only can oak trees hint at where property lines used to be or act as living fence rows, but in the past they have also been used as signals for roads and springs.

“These old oaks are just indicative of something that has been around for a long time now,” Beattie says. “Some of them are signal trees. Not every one we're seeing, obviously, but some of them out there could have been bent over and tied down by native peoples or even others at times to indicate a path along an old road.”

Beattie says this route can say a lot about Austin history, including things that have been glossed over in the past–like slavery in Austin’s outskirts.

“With that is the estimate of the percentage of folks who lived in the Dove Springs area in the 1860s, there was probably more like two or three times as many enslaved people as there were white folks living here,” Gonzales says. “People talk about Austin as not having quite a higher percentage of enslaved folks, but Southeast Austin did have more of that.”

The pair say the Camino Real lives on today through many of Texas’ popular interstates including I-35 between San Antonio and Austin. However, constant infrastructure changes and rapid growth in these larger Texas cities can compromise the history of the trail.

“That's the kind of thing we have to talk about with the Camino, because particularly between here and San Antonio, there's all this development going on all the time,” Gonzales says. “And little bits and pieces of the road are being lost.”

Some of the Camino Real trail sits on private land, limiting what can be done to stop further development. With this in mind, Gonzales and Beattie are working on ways to inform developers on the value of the Camino Real so the erasure of the trail’s history is minimal.

Beattie (left) and Gonzales (right) look through aerial maps on a laptop. Finding old trails often begins inside, pouring over archival material.

“Right now, we're actually working to create a report that will focus on the trail between San Antonio and Austin that will be shared with elected officials, planning departments, parks, departments, developers, so that they can see and understand, ‘Look, there's something here,’” Gonzales says. “And even though we might develop this small stretch of property, we can protect this archeological remnant and actually benefit from it.”

There’s always something new to be unpacked when doing the historical research Gonzales and Beattie do. Beattie says learning about the history of where you live can give you a different perspective on what shaped the town into what it is today.

“You can kind of see the layers of the past,” Beattie says. “There's something in the past that's the reason why this is a good place to make something appear here tomorrow, you know, is in the place itself.”

Community journalism doesn’t happen without community support.

Got story ideas, advice on how we can improve our reporting or just want to know more about what we do? Reach out to us at news@klru.org.

And if you value this type of reporting, then please consider making a donation to Austin PBS. Your gift makes the quality journalism done by the Decibel team possible. Thank you for your contribution.

More in Culture:

See all Culture posts

Contact Us

Email us at news@klru.org