A Happy Kitchen

For years, Grace Rivera Curry cooked up what she called her ‘go-to recipe,’ a savory concoction that used layers of chicken, jalapeños and cheese to cover up her lack of culinary know-how.

“It would make me look like a good cook,” Rivera says.

Growing up as a self-described tomboy, Rivera spent more time putting up drywall than putting dishes in the oven. But being diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes motivated Rivera to start expanding her food knowledge base. She had seen family members and neighbors in her Del Valle neighborhood struggle with the chronic disease.

Grace Rivera Curry slices up jalapeños in the kitchen of her Del Valle home. A self-described tomboy, Rivera didn’t dive into cooking until after she was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes.

“There are several members of my family who … had to have leg amputations,” Rivera says. “You go through the personal denial and … then you go, OK, I can't fall back anymore. I gotta keep going forward.”

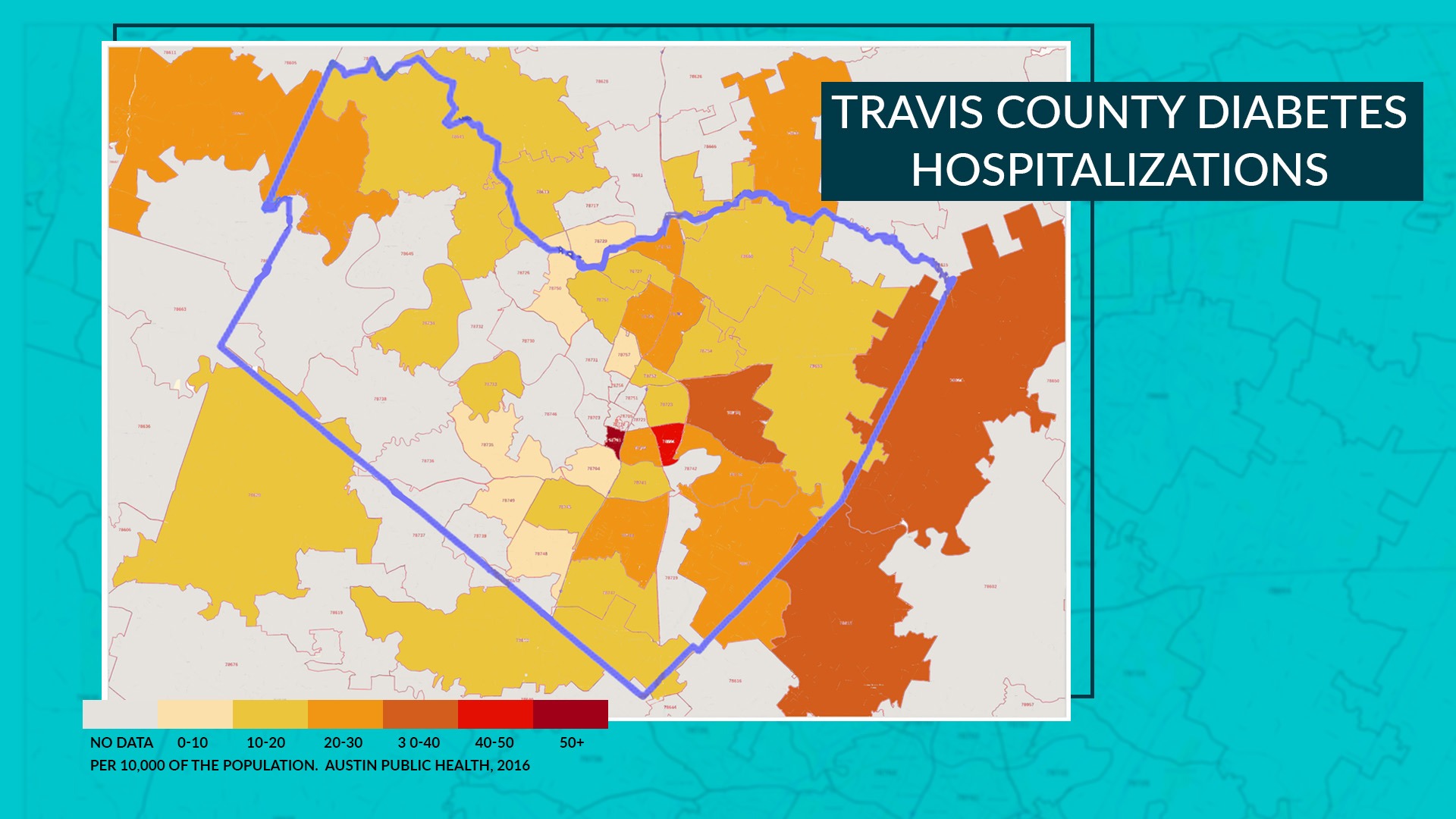

Rivera is not alone in her struggles. Texas has a higher rate of diabetes at 11.2% than the national average of 9.4%. Travis County holds to that trend. In it’s 2017 Critical Health Indicators Report, Austin Public Health reported the rate of diabetes for Black and Hispanic residents was nearly double that of white residents. That increases the odds of it being an issue for Del Valle residents, where the population is predominantly Hispanic.

A map of the rate of hospitalizations caused by health issues due to diabetes. The rate is per 10,000 of the population. This data was gathered in 2016 by Austin Public Health.

Diabetes also doubles a person’s chances of having heart disease or a stroke, which is the second highest cause of death in Travis County, right behind cancer. To push back against these diseases, health experts advise things like managing stress, moving more and eating better.

An educator by trade, Rivera decided to arm herself with knowledge about the topic she knew the least about — cooking.

“I found this particular organization was offering some different types of free cooking classes, depending upon what your economic level was and what areas of town you were in,” Rivera says. “I went to one class and I went, ‘Wow, that's pretty good.’ And then I said, ‘Well, what else do you have?’”

The organization Rivera discovered was the Sustainable Food Center and the classes were part of The Happy Kitchen/ La Cocina Alegre program. Started in 1998, the free bilingual program works with partner agencies like H-E-B and Foundation Communities to identify communities in Austin impacted by diet-related disease. The six weeks of classes focus on healthy eating and nutrition. At the time, participants would gather in neighborhood locations like churches or libraries. Groceries used in the demonstrations were handed out at the end of class so students could recreate the recipes at home. Adriana Botello de Prioleau is the education manager for the Sustainable Food Center and says the ultimate goal for the classes is to improve nutrition through knowledge.

Rivera (center) volunteers at a booth at the Sustainable Food Center Farmers’ Market at Sunset Valley. She discovered their Happy Kitchen/ La Cocina Alegre program in 2010 which emphasizes learning how to cook affordable, nutritious meals.

“If you know how to cook,” de Prioleau says. “You have a better chance to have good nutrition.”

But part of getting people onboard for the classes is meeting them where they are, according to Maddie Townsend, the food access and education coordinator at the Sustainable Food Center.

“It’s not necessarily telling people, ‘You can’t eat this. You can’t eat that,’” Townsend says. “It's adopting these recipes to be what works for you.”

Rivera stands by a planter tub of squash in her backyard, gesturing to where she plans to expand her garden. Del Valle is considered a food desert, and gas stations remain the closest option for any kind of groceries. “It's a systemic view that one has to take,” Rivera says. “You have to think about infrastructure. You have to think about education. You have to think about community involvement and whether or not there's food accessibility.”

That philosophy of gradually working in healthier options stood out to Rivera when she took the classes. Don’t like brown rice? Try mixing it in with white rice. Don’t want to sacrifice flavor? Maybe use a smidge less salt and use some fresh herbs instead.

“It's about transitioning,” Rivera says. “I think so many people … don't want to be preached to in a way that makes them feel like, oh, well, I was doing it wrong. And that's not what the classes are about at all.”

After taking several courses, Rivera was brought on as a volunteer instructor for The Happy Kitchen/ La Cocina Alegre.

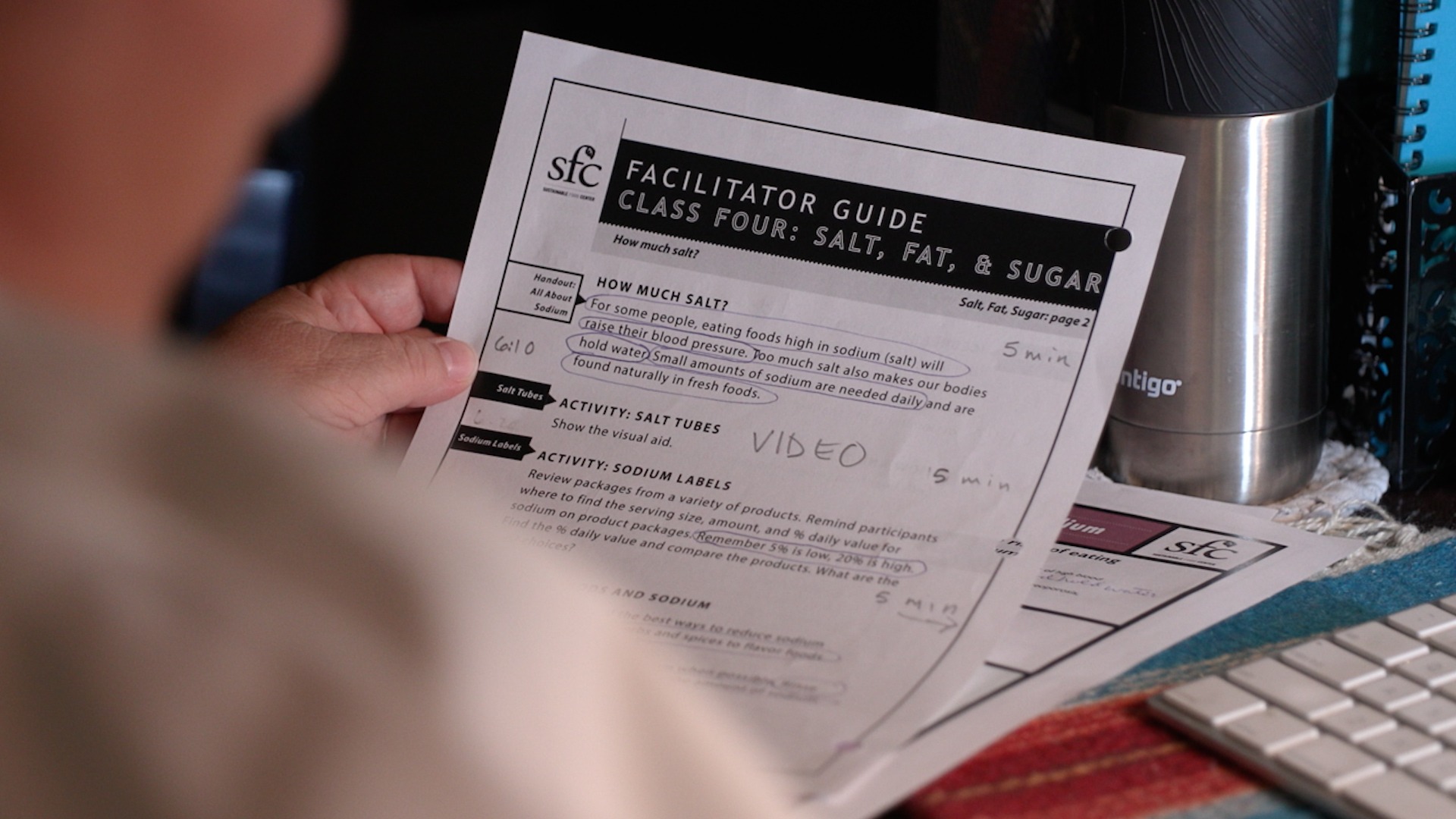

Rivera goes over her notes for The Happy Kitchen/ La Cocina Alegre virtual class. Since starting as a student, Rivera has gone on to work as a volunteer education facilitator for their classes.

“I have some friends who will joke, ‘Really, you're teaching a cooking class?’” Rivera says. “Yes. Yes, I am. Thank you very much. I'm teaching the basics, OK?”

Since 2015, Rivera has helped teach residents around Austin and in her neighborhood the same healthier cooking skills she picked up. Her previous job as an online education facilitator came in handy when the class switched to virtual meetups at the beginning of the pandemic. Rivera loves sharing her knowledge with her neighbors, but says issues surrounding health outcomes go beyond what can be touched on in an hour-long cooking class once a week.

“It's a systemic view that one has to take,” Rivera says. “You have to think about infrastructure. You have to think about education. You have to think about community involvement, and whether or not there's food accessibility.”

Accessibility to fresh produce remains an issue in Del Valle. The area is designated as a food desert. Gas stations remain the closest grocery shopping option for residents. While many carry canned goods and produce, it's a small selection compared to a grocery store. And diet is only one facet of a person’s overall health. But de Prioleau says even with limited local options, people can still make small changes to positively impact their health.

“It is much better to eat a can of green beans than don't eat anything,” de Prioleau says. “So wherever you are right now in your diet, if you have a chance to fix it a little bit better, you can do it.”

For her part, Rivera plans to keep sharing her knowledge with her neighbors around Austin and in Del Valle, as the Sustainable Food Center considers another round of classes for the area in the spring. She hopes attendees walk away with not just a bag of groceries and some new recipes, but also a desire to share that information with family and friends.

“We’ve got good people in Del Valle,” Rivera says. “I just want what’s best for my community.”

Community journalism doesn’t happen without community support.

Got story ideas, advice on how we can improve our reporting or just want to know more about what we do? Reach out to us at news@klru.org.

And if you value this type of reporting, then please consider making a donation to Austin PBS. Your gift makes the quality journalism done by the Decibel team possible. Thank you for your contribution.

More in Health:

See all Health posts

Contact Us

Email us at news@klru.org