‘The Status Quo Is Just Not Sufficient’: Austinites On HOME And Affordability

Standing in the morning light of the city hall atrium, Daniel Kavelman laments the lack of affordable housing in Austin.

“We've seen an enormous increase in housing costs,” Kavelman says. “As demand to live in central Austin has gone up, we're finding that the land costs have gone up immensely.”

Amanda Carillo agrees. A longtime Austin resident, she too is concerned about rising costs.

“That's the dream of being able to come and buy a home and have stability and have generational wealth,” Carillo says. “But we can't do that because they make poor decisions like this to push us out.”

Carillo is referring to the Austin City Council and their decision to pass the HOME initiative earlier this month. The land code update allows for more structures to be built on a single lot in an effort to increase housing stock. But this is where Carillo and Kavelman’s consensus ends. While they, like many others, agree Austin’s housing costs are astronomical, they are strongly divided on whether the HOME Initiative will fix these problems or make them worse.

People for and against the HOME initiative fill the council chambers to capacity on December 7th. Public testimony lasted more than 12 hours.

HOME stands for Home Options for Middle-Income Empowerment. It will allow up to three homes to be built on lots zoned SF-1, SF-2 or SF-3 without having to get them rezoned. It also increases the number of unrelated people allowed to live together. Proponents say the ordinance will boost housing for middle-income families. City Council Member Leslie Pool authored the ordinance. At a press conference in early December, she pointed out that since she took office in 2015, housing prices had doubled.

“The median home price was $238,000, and there were a lot of options in almost every neighborhood,” Pool said. Now, “the median home price in Austin is $540,000 – well beyond the reach of a middle-income earner whose price point is limited to $350,000.”

A family would need to earn roughly $180,000 per year to afford a median home in the city. And while rent has dropped, it still averages around $1500 per month. It’s an issue seen across the country. For renters in the bottom 20% of incomes, a majority of them pay more than half their income on rent and utilities. That’s according to a study from the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies. Many residents struggle to make ends meet.

“I really have had cadets tell me that they are choosing between gas, groceries and paying rent and keeping their lights on,” says Selena Xie, president of the Austin EMS Association. She says in a recent contract negotiation, they discovered 80% of their medics don’t live in Travis County. “We have medics that are coming here looking for really cheap housing, wanting those options, and they don't really exist.”

But opponents say what’s considered ‘cheap’ really depends on your paycheck. Stephanie Thomas is with ADAPT of Texas, a disability rights group. She says the incomes of those with disabilities and their caretakers can be well below the average.

“The people that we represent, most of them their incomes are below 15% of the median family income. And when they talk about affordability, they're usually targeting 80% of the median family income,” Thomas says. “Things don't trickle down that far.”

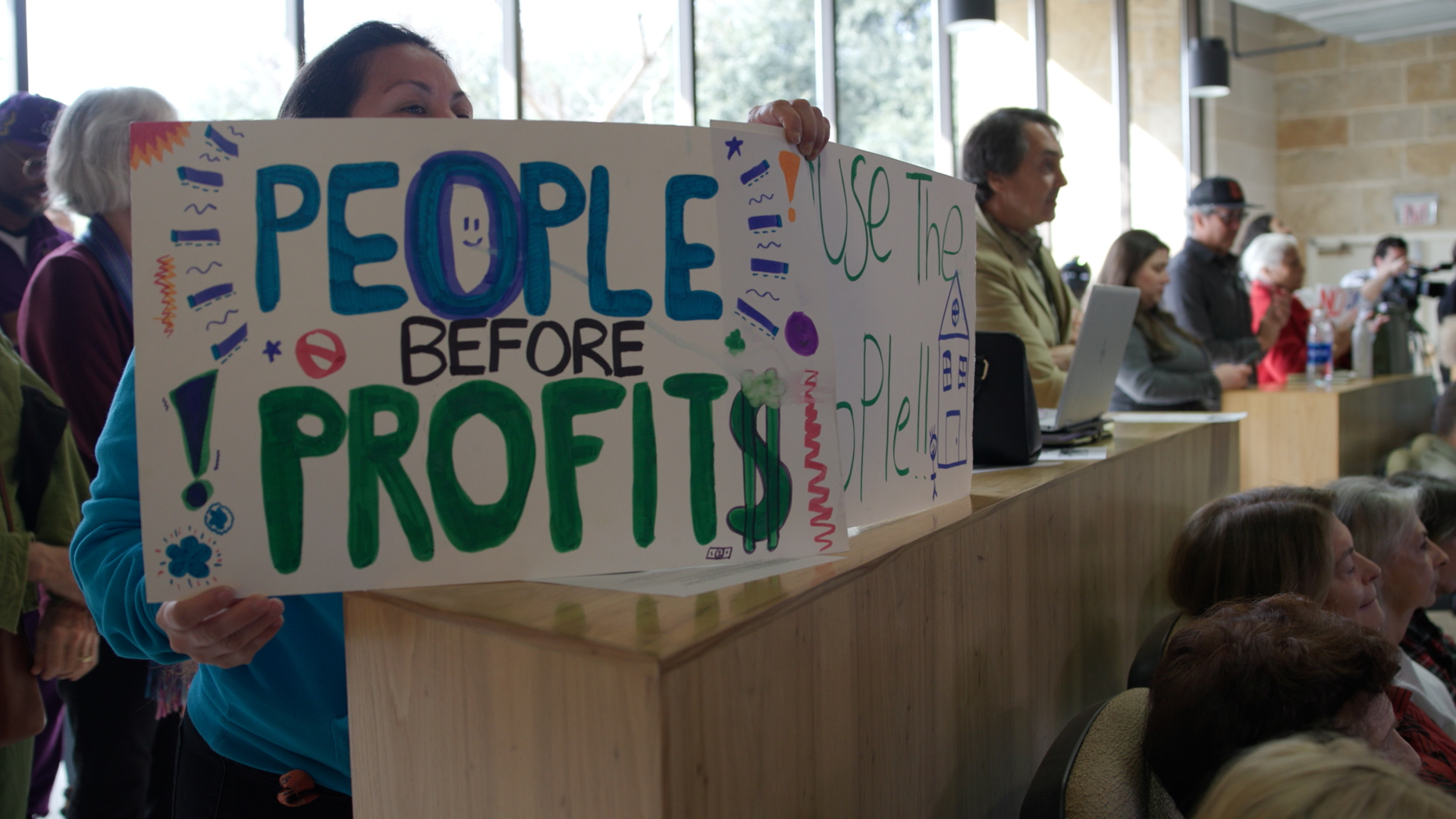

A woman holds a sign in opposition to the HOME initiative. Many residents are worried this will increase gentrification in Austin’s eastern crescent.

Nyeka Thomas agrees, believing housing will still be too expensive for many families already facing displacement.

“I don’t even make $65,000, or $85,000, our teachers don’t even make that, let alone single parents,” Thomas says. “So those units … it’s not for east Austin, it’s not for black or brown people that lived in east austin and are displaced from east Austin.”

But those in favor of HOME say because the initiative is city-wide, it won’t cause a land run on a specific neighborhood. Zach Faddis is with AURA, a grassroots organization pushing for land use and transportation improvements.

“There's not some huge pressure to build on this lot because they can do it on any lot,” Faddis says. “It allows neighborhoods to be more welcoming for people in a lower income level and it reduces housing pressure on everyone around you.”

But critics have pointed out that the ordinance doesn’t have specific language around affordability that might help prevent displacement. Ana Aguirre is with Community Not Commodity and the Southeast Neighborhood Contact Team, and she’s opposed to the HOME ordinance. She believes the new land use rules will increase property taxes and accelerate gentrification.

“We already have predatory people or individuals or companies that are already reaching out to residents in the Eastern Crescent offering to buy their backyards for $100,000,” Aguirre says. “The council needs to protect Black and brown communities that have been gentrified.”

A Lego house is displayed in the city hall atrium. Advocates say increased density and housing stock will reduce housing pressures across the city.

City hall staffers issued a report earlier this year stating that the ordinance could increase displacement in marginalized communities. And while research shows that adding more housing can bring costs down, studies show that it’s unclear if those prices help lower income households. The city council did approve an amendment that incentives preserving at least half of a home if it was built before the 1960’s. Faddis says that while the initial homes may not be accessible to lower income residents, increasing the overall stock will eventually lead to more publicly subsidized housing.

“We should be doing a lot more … building publicly subsidized housing,” Faddis says. “But one of the best ways that we can raise revenue to allow yourself to have more options as far as to build affordable housing is by allowing market rate development. They do not conflict.”

Aguirre also voiced concerns over the environmental impact of increased housing density. She lives in southeast Austin and has seen the fallout from historic floods in 2013 and 2015. She’s concerned that more impervious cover will mean more runoff and potentially more flooding.

“And that's the worst case scenario,” Aguirre says. “Not just loss of property, but also loss of life.”

Proponents have said denser housing is better for the environment. In a letter supporting the initiative, Environment Texas executive director Luke Metzger said urban density could “curb the flow of polluted runoff into streams and lakes,” as well as cut carbon emissions. Kavelman says that there will also be room to study and improve impervious cover.

“[City staff] have already convened a lot of environmentalists together to work on how can we be creative to make sure that our aggregate amount of impervious cover does not go up,” Kavelman says. “This is good climate policy.”

Aguirre remains skeptical.

“Until I see it in writing, I don't believe it,” she says.

Public comments on the ordinance touched on all these issues and more, over the course of 12 hours. Ultimately two council members voted against it: Mackenzie Kelly and Alison Alter. New construction projects are expected to begin under the ordinance next February. Phase 2 of the HOME initiative is expected to be up for consideration next year. In the meantime, those for and against the measure have little they can agree upon, except for two things: Austin is pricey, and it’s not getting better.

“The status quo is just not sufficient. It's not cutting it,” says Xie. “So I'm willing to try anything that potentially increases the housing stock.”

Community journalism doesn’t happen without community support.

Got story ideas, advice on how we can improve our reporting or just want to know more about what we do? Reach out to us at news@klru.org.

And if you value this type of reporting, then please consider making a donation to Austin PBS. Your gift makes the quality journalism done by the Decibel team possible. Thank you for your contribution.

More in Politics:

See all Politics posts

Contact Us

Email us at news@klru.org