She Helps Families With Any Resource They Need. Lately They Need Help Leaving.

Students share smiles with Sonia Hernandez as they file into her classroom. They pull out notebooks and pencil cases as she begins writing phrases on a dry erase board. It looks like any scene from any classroom, except these aren’t traditional students. These are parents taking ESL classes at Palm Elementary. As the school’s parent support specialist, it’s just one of the many wraparound services Hernandez assists families with.

“Food, resources, transportation, legal advice, medical,” Hernandez says. “Any resources that they might need … that's what we assist them with.”

But the biggest need is housing. Hernandez says many families are struggling to find affordable places to stay. Wait lists are long for housing programs. Families with undocumented members face even more hurdles, as programs either offer less assistance or are inaccessible. Many families are forced to leave the district, which also means leaving the support services provided by Hernandez and the school.

“We've lost a lot of kids,” Hernandez says. “Yes, we have beautiful apartments being built around our community, but still it's not affordable for our families.”

Students walk the halls of Palm Elementary. Many students have left the school because rising housing costs have pushed their families out.

Just over 87% of students at Palm Elementary are considered economically disadvantaged. That’s well above the 50% average for the entire Austin Independent School District. But housing options for students and their families are limited. A recent report by the Austin Board of Realtors showed the city is short roughly 170,000 homes for families making 60% or less of the median family income. Travis County overall fares slightly worse, with a shortage of roughly 199,000 homes for lower income families. That leaves many families looking for assistance, which has challenges of its own.

“Demand is probably the number one challenge,” says Michael Roth, vice president of Pathways Asset Management Inc., the property management and operations arm of the Housing Authority of the City of Austin, or HACA. They manage 18 apartment complexes, as well as the federally funded voucher program and community housing resources. Between all these programs, Roth estimates they help house about 25,000 residents each night. And it’s still not enough.

“There's more than 10,000 families on the waiting list for 1,800 apartments,” Roth says. The Housing Choice Voucher Program, also known as Section 8, also is in high demand. According to HACA’s website, the voucher waitlist last opened in 2018.

“We have to have a realistic waiting list,” Roth says. “We could do a waiting list and take in 20,000 people. But that's not realistic for those families. That's offering false hope.”

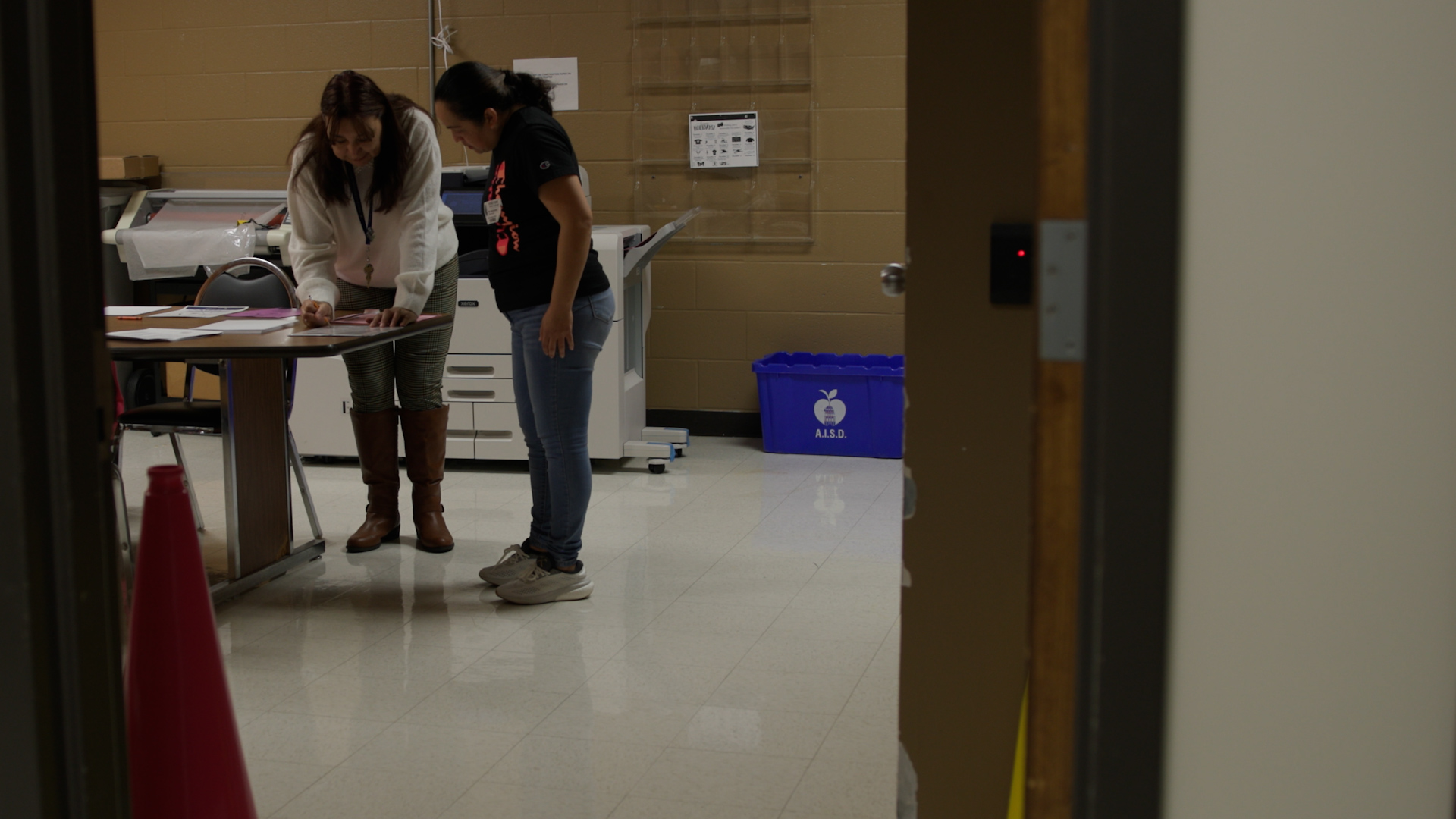

Sonia Hernandez (left) reviews a paper with a parent. Hernandez says it can be very difficult to secure housing for families.

Hernandez says she often helps people fill out housing applications. But they can face barriers if family members are undocumented.

“A lot of these people are not paid with checks, they're paid with cash,” Hernandez says. “And a lot of programs require either some type of statement, your income tax, a lot of these people don't do income taxes. So that is what makes it hard on them.”

Even if an employer is willing to vouch for workers, they may not qualify for some programs. At least one family member must have legal status in the United States to apply for federal housing assistance. If they meet those qualifications and get off the waiting list, they will pay more than a similar family in which everyone has legal status. If a family of four paid $200 for rent, a family with one undocumented member may pay $400 because they only receive 75% of the subsidy.

“They get less subsidies prorated based on the ratio of eligible and not eligible family members, Roth says. “It can be as much as double. And so that has a significant impact on their finances.”

It can also impact where families end up living. Gabriela Garcia is a project coordinator with BASTA, a tenants rights advocacy group.

“As there are fewer opportunities for affordable housing people are looking for just any place to go,” Garcia says. Families may end up in places that try to take advantage of the situation by adding fees to the rent, or locations that don’t maintain livable quarters. But depending on a tenant’s status, they may not feel comfortable speaking up.

“A lot of things that stop tenants from speaking out,” Garcia says. “In general, it happens to all tenants because the landlord has the power to evict, and that's huge.”

Hernandez (right) teaching an ESL class for Palm Elementary parents. As a parent support specialist, Hernandez says her job is to connect parents with any services they might need.

It’s a concern that Hernandez knows very well.

“It's so hard for me to do something,” Hernandez says. “I need to just try to be very careful because what if they throw them out? Where am I going to put them? You know, then they'll be out there with children.”

Whether families are forced out due to eviction or increased costs, area schools still lose students. Currently there are 349 students enrolled at Palm Elementary. Ten years ago enrollment was at 531. Hernandez says while she can help with bussing, it can sometimes take hours for students to get to and from school.

“I'll tell them, the wise thing to do is just put them in whatever school is closest to you,” Hernandez says. “[But] a lot of programs, they don't have that we have available.

According to the Texas Education Agency, Title I, Part A schools with entitlements over $500,000 must set aside funds for parent and family engagement activities. While schools could use those funds to hire a parent support specialist like Hernandez, they are not required to do so.

Relocations not only shrink the size of the school, but also pull at the fabric of the community, according to Garcia.

“You have your community here. Maybe you had a family or neighbors that were helping with childcare,” Garcia says. “All of those little things add up.”

Experts don’t see Austin’s housing crisis letting up any time soon. A new report shows that the city is far behind its goal for building more affordable housing. Some city council members and citizens hope the new HOME initiative, which will go into effect this year, will help ease Austin’s housing pressures by quickly adding smaller, more affordable units. But opponents to the measure are concerned it will ramp up gentrification. In the meantime, Hernandez continues to help her parents with housing, or anything else they may need, no matter where they end up.

“I've told all of the families, don't think that because your kids are no longer in our school [that] you cannot come to us,” Hernandez says. “This is not about what is your immigration status, but who you are as a human being.”

Community journalism doesn’t happen without community support.

Got story ideas, advice on how we can improve our reporting or just want to know more about what we do? Reach out to us at news@klru.org.

And if you value this type of reporting, then please consider making a donation to Austin PBS. Your gift makes the quality journalism done by the Decibel team possible. Thank you for your contribution.

More in Education:

See all Education posts

Contact Us

Email us at news@klru.org