Influence At Work

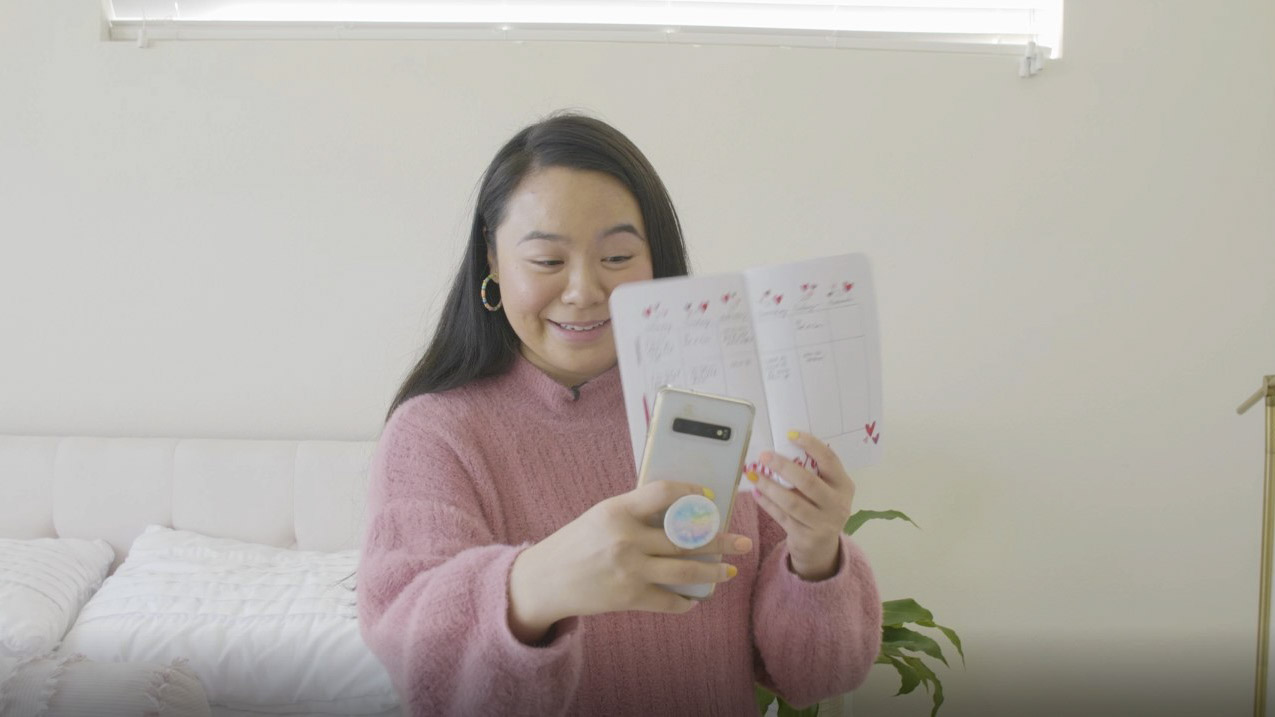

The ink has just dried on the bullet journal that Sarah Wong is holding. Adorning the pages around the neat calendar blocks are dozens of sketched hearts, filled with varying shades of pink. At the bottom of the pages, scrawled in immaculate cursive, is the word “January.”

“I typically wouldn’t do a heart spread in January,” Wong says. “But a lot of my clients are currently focused on Valentine’s Day.”

With that, she stops recording on her phone. She’ll soon upload the video, along with some how-to bullet journaling tips, to her more than 5,000 followers on Instagram.

“Instagram is where I try to give people behind the scenes look at what’s happening in my everyday life,” she says. “And then Instagram is also my favorite place to share all of my bullet journals because people end up saving and they like to scroll and get inspired.”

Wong runs a blog called The Bella Insider, which aims to provide tips for women who are recent college graduates.

Sarah Wong records a video for Instagram featuring one of her bullet journal creations. Wong runs a blog called The Bella Insider, which seeks to help women transition into adulthood after college graduation.

“The blog now focuses on helping women transition out of college and giving them resources, both kind of fun and playful stuff like apartment decor and organization into the more serious things like budgeting and preparing for your first job,” she says.

Wong is trying to maintain her position in what has now become a multibillion dollar industry. Brands are expected to spend up to $15 million on influencer marketing in 2022.

“It will probably seep into everything, and it is already seeping into everything, so I think there’s a lot more room for the influencer industry to grow,” says Robert Kozinets, a professor at the University of Southern California.

Kozinets has been studying how the internet is changing the marketing industry since the late 1990s. He began teaching an influencer course at USC in 2019 because he saw the need to conceptualize this growing market and treat it as a serious phenomenon. Even a clear definition of the work needs greater understanding. People often define an influencer as someone who has influence over other people, but Kozinets says the work is more complex than that.

“The core of it is that they are intentionally drawing an audience and that they are doing it in a genuine and authentic way. For example, Clint Eastwood posting as Dirty Harry is not an influencer because he’s playing a role,” he says. “If celebrities are posting as themselves, like Selena Gomez kind of of giving you a behind the scenes look, she can be a celebrity and an influencer. But she can’t be posting as one of her roles because that’s not the authentic thing. People are looking for this sort of sense of authenticity.”

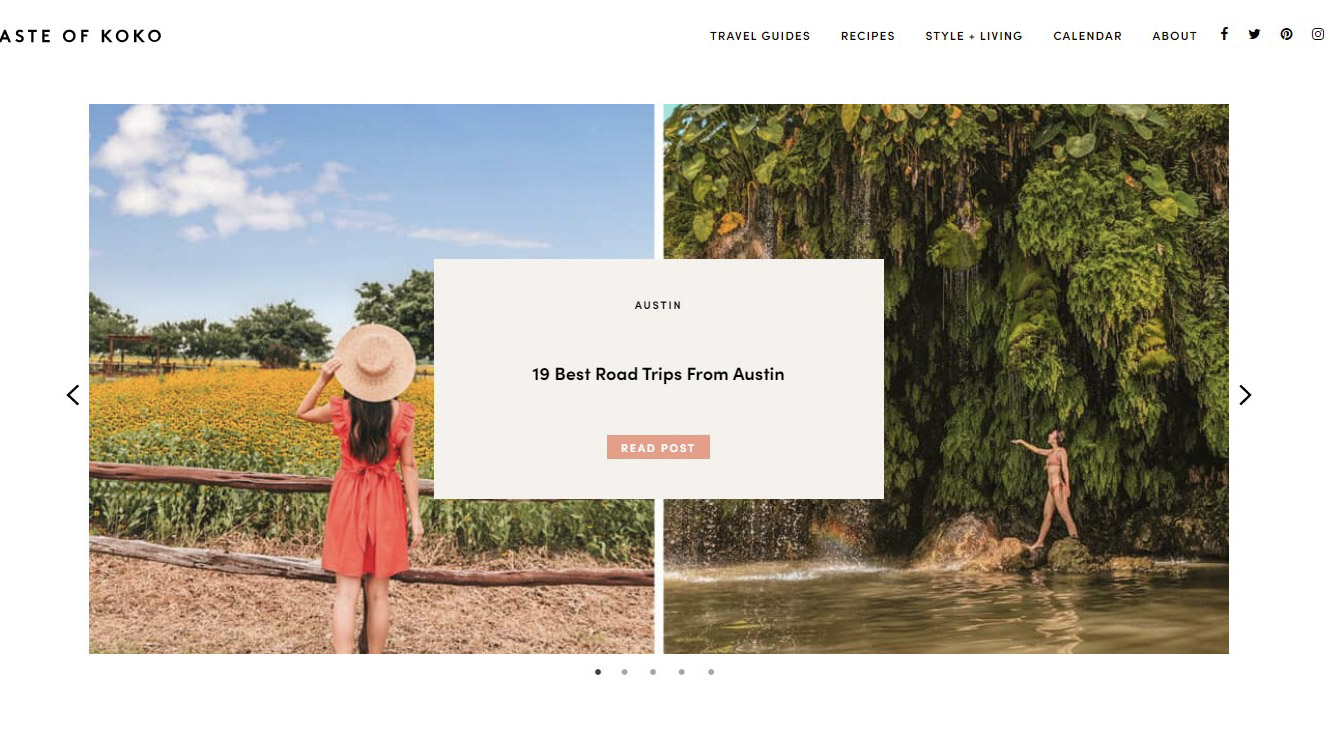

Food blogger Jane Ko is considered one of the pioneering influencers in Austin since she started this work 10 years ago just as the market was beginning to take shape.

“My brand and my website just happened to be at the right place at the right time when Austin became on the rise and brands from an advertising standpoint wanted to tap into this demographic,” she says.

Homepage of the A Taste of Koko blog. Jane Ko started the blog in 2010 and today has more than 90,000 followers on Instagram.

Today, her blog A Taste of Koko has become a huge success, with features in publications such as O Magazine and Instyle, and brand partnerships with companies like IKEA and Target. But it took Ko years to establish herself and she finds people often misunderstand just how hard this work can be.

“Certain influencers do disclose how much money they make and then people are like, ‘Oh that’s so unfair.’ Whereas you don’t judge someone who is maybe a CPA making 200K a year. You would never say to them, ‘Hey that’s unfair,’ or ‘how do you get paid that much’ or all these things,” Ko says. “The whole stigma of being an influencer and the whole state of influencing is that it’s easy. But it’s not.”

Influencers can often work 12 hours a day in order to produce their content. Traditional media organizations usually have individual staff members who each manage different aspects of content creation like building a website or taking photos. Influencers, instead, often do all of that work on their own.

“It seems frivolous and light because you’re looking at a cute little video about toys,” Kozinets says. “But to do that video required a lot of research, a lot of connection and all the production stuff and then all the stuff you don’t see afterward working with your followers and getting their feedback, and responding to that and building that. It’s very, very hard.”

One of Sarah Wong’s posts via her Instagram handle @sarah_thebella. “Instagram is also my favorite place to share all of my bullet journals because people end up saving and they like to scroll and get inspired,” she says.

Kozinets hopes his class will help show the work behind the glossy photos and posts. That’s why he’s currently writing a textbook so others can have guidance on how to teach a course like his.

“This is a huge industry and it’s also incredibly impactful. It’s having all kinds of impacts not only on industry, but also on our culture. We all sort of know that, so we need to be teaching people about this because the implications are very strong,” he says. “So I don’t just teach students how to run a campaign. I also teach them what are the ethical implications? What are the legal obligations and how is this changing culture? How are the hidden power relations in the influencer industry, for example, hiding things like gender, race and body image?”

Those cultural implications came to a head last year following the killing of George Floyd and protests from the Black Lives Matter movement when, like most media organizations, the influencing world was criticised for its lack of diversity. Shruthi Parker runs a lifestyle blog called The Honest Shruth, which covers topics like marriage, motherhood, food and faith. Parker says she faced challenges being an Indian-American woman in this field.

“This is not an industry for minorities. It is an industry that is absolutely tailored to the white woman. And I can say this because I’ve been in it and I’ve seen it,” she says. “People like me are not exactly welcomed in this industry. We’re having to work twice as hard to get the same amount of recognition or brand deals.”

While many Asian Americans have seen great success as influencers, those people often fit into a stereotypical look. Ethnicity, skin tone, hair texture and body type can all affect who gets selected for a brand deal. Wong, who is of Chinese descent, says different body types, for example, aren’t represented well in the industry.

The Honest Shruth is a blog created by Shruthi Parker. The blog covers topics such as motherhood, marriage, faith, travel and more.

“When I look at brands who are working on really large campaigns and they are inviting their influencer community, I still don’t really see that many Asian women who are plus sized or maybe just look different,” she says. “For me, I’m 5’1”, but I’m technically overweight because I used to be a gymnast and a lot of that muscle turned into not muscle, and I’m still kind of itching to see other women who have different body types and looks different than the average person of color who has made it in this industry.”

Parker agrees and hopes the industry will grow to highlight the diversity within the Asian American community.

“We are still very different people. You know people say, 'Oh she’s South Asian.' That incorporates like 10-12 countries. And so I’m hoping that like we say to everyone, ‘Oh, like increase your diversity.’ Even within the Asian American sphere I’m hopeful that we can start reaching across the aisle and building each other up there too.”

While there’s still much progress to be made, Wong is happy to move the influencer field forward in her own way.

“I think creating content and being able to use yourself and your platforms to spread a message is a place of privilege,” she says. “And to sit in a place of privilege means, for me, it means to show a good example.”

Community journalism doesn’t happen without community support.

Got story ideas, advice on how we can improve our reporting or just want to know more about what we do? Reach out to us at news@klru.org.

And if you value this type of reporting, then please consider making a donation to Austin PBS. Your gift makes the quality journalism done by the Decibel team possible. Thank you for your contribution.

More in Science & Technology :

See all Science & Technology posts

Contact Us

Email us at news@klru.org